Appointed Times

In the previous article we introduced the Moedim and how this ‘pattern’ speaks of Jesus. Here we continue to explore the wonderful truth that they speak powerfully of Jesus’ life, mission and ministry

The Bible’s calendar is a lunar calendar. The “year” that the Bible marks is the agricultural year and based around harvesting. So we can “plot” graphically how the Biblical year looks, by comparing it with the ‘solar’ year – the year based on the sun. We all think, naturally, of a twelve month cycle beginning in January. That is the solar year. From a Biblical perspective, it is also the pagan year!

A calendar can be viewed in more than one way. The normal “western” year reflects the Gregorian Calendar beginning in January and ending in December. Whilst it may be relatively unimportant, it is worth noting that this Gregorian year also – in a very real sense – reflects a Pagan year, as each month name corresponds to a Pagan (Roman) “god”. Certainly God wants us to have nothing to do with Paganism, yet God’s children are obliged to live within the system common to mankind’s various cultures. We can reflect, as well, that every religion and culture has its own calendar, usually based on lunisolar principles, but with notable variations. God’s calendar for His Chosen People would, in practice, have many competitors! Unlike the Pagan calendars, however, the Hebrew calendar represents two unique things:

■ it speaks of the life, death, resurrection and completed mission of one Man.

■ it speaks of the history – and especially of the future – of the whole of Mankind.

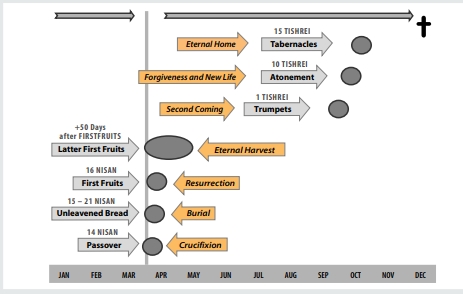

So in our diagram, based on the one in the previous article (issue 14:5 Sept/Oct 2019) we see at a simplistic level two things: firstly the normal Gregorian calendar of twelve months along the bottom horizontal line, and secondly a vertical line between March and April that signals the beginning of the Hebrew agricultural year. On this basic ‘template’ we can “plot” the key events of the Hebrew calendar, as measured from God’s perspective.

So in our diagram, based on the one in the previous article (issue 14:5 Sept/Oct 2019) we see at a simplistic level two things: firstly the normal Gregorian calendar of twelve months along the bottom horizontal line, and secondly a vertical line between March and April that signals the beginning of the Hebrew agricultural year. On this basic ‘template’ we can “plot” the key events of the Hebrew calendar, as measured from God’s perspective.

Times and Seasons

The basic Moedim Pattern from Leviticus

To follow God’s pattern for life in the annual calendar set out in Leviticus 23, we need to use a lunar calendar, where each month begins when the new moon first appears in the night sky, and each ‘day’ begins at nightfall (Genesis 1:15). God ‘appointed the moon for seasons’ (Psalm 104:19) (1) so each Biblical Feast occurs on days set by the lunar calendar. Is the Biblical calendar still important to God, or has it been ‘replaced’ in some way? Since the Biblical Feasts mark out the “high points” of God’s redemptive purposes and also express God’s view of the history of mankind, it is superfluous to ask if His calendar and His appointed festivals are still important. Rather, we should be asking how do they speak to us today? The Lord Jesus died on the ‘Feast of Passover’ and was raised from the dead on the ‘Feast of First Fruits’. The Holy Spirit was poured out at the ‘Latter First Fruits’ (2) as the inauguration of the time of the New Covenant, when God’s Spirit would be poured into the lives of Jesus’ disciples. We can say with certainty that Jesus fulfilled the prophetic meaning of these ‘Feasts’ on the actual days they occurred.

The Biblical feasts, as given to Moses in Leviticus 23 (and reemphasized with minor variations in Exodus 12, Numbers 28-29 and Deuteronomy 16) are the ‘Moedim’ which means, as we have seen, ‘appointed times’. These times were appointed by God for a special revelation to the whole of mankind, and for something specific to be done. God graciously gave to the Hebrew people precise instructions about what should happen at these ‘holy convocations’, so that He could reveal truths about Himself and His plan to bring people into His Kingdom, not only from Israel but from every tribe and tongue.(3)

These Moedim are sometimes referred to as the Biblical feasts or festivals, as a sort of ‘shorthand’ title. In contemporary usage “festival” usually refers to activities over a period of time whilst “feast” indicates one part of the celebration, often a meal. In religious usage, both modern and ancient, these two words tend to be used quite interchangeably. The Jews used the word Moed (“assembly” or “convocation”) and hag4 for their important celebrations. Feasts of a more private nature were called mishteh. Perhaps confusingly, the majority of English language translations of the Bible do not differentiate between these words. The recent One New Man Bible (2015) tends to use the modern Hebrew equivalent for individual Moeds so it is clear which Moed is being referred to.

The seven Moeds take place in two ‘clusters’. The first three occur in the spring, the fourth in early summer and the final three in the autumn. At His first incarnation, Jesus fulfilled the symbolic message of the spring feasts on the precise days preordained by God the Father. We know what those days were, even if we debate the precise year in which they occurred! The symbolism of the autumn Moeds has yet to be fulfilled in their entirety. They point to the future. In John 7:37-39, as Jesus spoke at the festival of Tabernacles, He promised “streams of life giving water” to those who come to Him, of which to “drink”.

As John writes, this was an allusion to the gift of the Holy Spirit, which all Believers freely receive. This reference to ‘living water’ reflects Zechariah 14:8 which hints at the second coming of Messiah. This in turn is mirrored in Revelation 22:1-2, which speaks of the future when streams of ‘living water’ will flow from the throne of the lamb.

Rosemary Bamber, in her book “In Time With God”, comments that Zechariah 14 connects the Feast of Tabernacles to the future rule and reign of Messiah on earth. She observes that the Moedim in the Biblical calendar represent a ‘timeline of history’, which simultaneously connects to the natural seasons and harvests in the physical land of Israel. So history and the seasons are connected. The beginning of this time-line concerns God’s plan to redeem and save our souls – through the perfect sacrifice of Jesus who takes away our sins and redeems us back to God. This act is represented in the first three feasts of spring. After this, through spring and early summer, as the barley and wheat harvests are gathered in Israel, we see the growth of the ‘redeemed congregation’, broadly in modern language, the church. We reflect that Jesus told His disciples to look and to see – not the harvest to come in four months time – but to recognize that the harvest fields were already “white” for harvest (John 4:35 and Luke 10:2). The hot summer months represent for us the time of the predominantly Gentile church. In the seventh month we reach the autumn feasts where the focus turns to the conclusion of ‘the time of the Gentiles’ (Luke 21:24), to God’s final purposes amongst the Jews, and to Jesus’ second coming. The key themes revealed through the Moedim, then, are (1) God’s plan of redemption, (2) the Kingdom of God which has room both for Jews and for Gentiles, and (3) the preparation of Jesus’ “bride” from amongst all nations.

The Jewish year reflects the seasons in Israel. It is to a large extent an ‘agricultural year’ in the physical realm. Yet it is also a ‘theological year’ in the spiritual realm. The year begins with Jesus the Lamb of God who fulfils the symbolism of the Lamb at the spring ‘Feast of Passover’. It moves on to the linked Moed of ‘Unleavened Bread’, which the Israelites were to eat for a period of seven days. The lack of leaven symbolises sinlessness, as we shall see later in this series. Jesus is our sinless Saviour. The Moed of ‘First Fruits’ reflects the joy of the early harvest – and the first fruit in the Kingdom of God is the risen Lord Jesus! He is the FIRST to be raised from death, but not the last! And so the spring festivals are concluded. The festival of ‘Latter First Fruits’ ( Shavuot in Hebrew) expresses joy at the anticipated later harvest. There is more than one legitimate way to understand ‘Latter First Fruits’, but the obvious way is to see these ‘fruits’ as being all those who place their trust and faith in the Jewish Messiah down through history until He returns. In the autumn we reach the final cluster of three Moedim. ‘Trumpets’ reflects the second coming of Messiah (naturally, at the end of the harvest), the announcement of which will be by the blast of shofarim (trumpets). ‘Atonement’ reflects the reality of forgiveness and new life. Finally, ‘Tabernacles’ is the joyful truth that Jesus and His disciples live in community forever, as He literally ‘tabernacles with us’. We can summarize these thoughts graphically as shown in the diagram.

This is the pattern used throughout this series. It is important to note that it is not drawn to scale! Hopefully it helps to “fix” the Moeds in our mind’s eye. Beyond knowing the approximate ‘position’ of the feasts, how they develop and the gap that sits between them (something that is important and which we will explore later) we can precisely state their dates, as is shown above the arrows in the diagram.

We continue this article in the next edition where we explore the timing of the Moedim.

This material is based on Peter’s book “The Messiah Pattern” published by Christian Publications International.

1 In the Good News Translation this is “You created the moon to mark the months” and in the New International Version it is “the moon marks off the seasons”. The One New Man Bible reflects: “He appointed the moon for seasons”.

2 The Christian church calls this, perhaps unhelpfully “Pentecost”.

3 Revelation 5:9 and Revelation 7:9.

4 The term hag indicates a festival usually observed by some sort of pilgrimage.